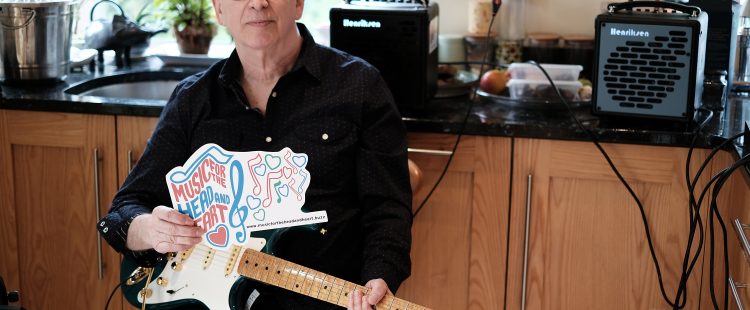

Nick Cody: Hi, this is Nick, and I am with Michael Ross from Guitar Moderne all the way from Nashville. Welcome to Yorkshire.

Michael Ross: It’s great to be here.

Nick Cody: And welcome to Music For The Head And Heart. I wanted to start off by asking you about Guitar Moderne, which I know is a site that you’ve been promoting. How long has that been going and what’s the thinking behind it?

Michael Ross: Well, it’s been going almost seven years now, something like that. I started maybe a year before I moved to Nashville. I had been spending a lot of time on YouTube looking for avant garde guitar players, people who are doing something different with the instrument, other than the normal shredding, riffing, things like that, getting new sounds, doing new approaches. It’s something I’ve always been interested in, in addition to being interested in roots music and blues and things like that.

Michael Ross: I was finding all these great players and all these great videos, and I was loving them, and I’m thinking, “Who can I share this with? I’m spending all this time,” and I thought about putting it on Facebook where I have a lot of guitar player friends, but only a fraction of those would be interested in this particular kind of guitar playing. We’re talking about people who are playing it flat on their laps, putting alligator clips on it, or are basically making noise with it, rather than notes.

Michael Ross: I thought about putting up a website, and thought I can aggregate the videos there, and if you build it, they will come, or not. I taught myself enough WordPress to put the site together and I started putting the videos up, and, low and behold, people started coming. There seems to be an interest in this worldwide and it seems to be growing. Eventually, I got advertisers, and now it’s been going for seven years. I do it whenever I can because I still write for Guitar Player and Premier Guitar, and I have a column in Electronic Musician. So, when I can spare time from all that, I try and post stuff, and I do interviews and gear reviews and things like that.

Michael Ross: I started getting into this through Norwegian guitar players. I discovered Eivind Aarset, who was playing with Nils Petter Molvaer. I was actually doing a session in San Francisco with a woman named Aina Kemanis, who’s a great singer. She’s been on ECM records with Barre Phillips. She heard the way I played and she said, “You know, there’s this guitar player you would really like, Eivind Aarset.” Then I discovered him on the the Nils Petter Molvaer Khmer album, an amazing record on ECM, which featured a separate album of remixes. Eivind was the guy who was playing through a laptop in addition to playing through pedals. He was a brilliant guitar player. I mean, he could shred with the best of them, but he was making as many sounds as he was notes.

Michael Ross: Maybe even before that, I had discovered Raoul Bjokenheim from Finland, who’s like if Hendrix met Ornette Coleman. And then I discovered Stian Westerhus from Norway, who really does largely play sounds. He’ll bow the guitar, but he is a master of pedals and does glitchy stuff. And then, there’s all these European guitar players. A British guitar player I’m going to meet with on Saturday, Leo Abrahams, does stuff like that, in addition to playing with Brian Eno and Bryan Ferry. There’s a guy, David Kollar, who sounds a lot like Eivind Aarset, who’s … I’m trying to remember where he’s from, but it’s an Eastern European country, Czechoslovakia or somewhere like that. Italian guitar players.

Michael Ross: They’re really are all over the world. A lot of them have moved to New York. This guy, Don Mount goes around to all the New York clubs and does a lot of videotaping of … Well, videotaping, I’m showing my age. He does a lot of recording of these avant garde artists of all kinds playing the clubs in New York, and he posts that I repost.

Michael Ross: Guitar Moderne, I think of it more as an aggregation site than an actual magazine. I mean, I do write for it. I do write intros to the interviews, but, at the beginning, I was just doing email interviews.

Nick Cody: So how’s technology changed music, and particularly avant garde music since you’ve been playing? Because, you know, you’ve been playing a long while.

Michael Ross: Technology has always changed music. It changed as soon as we started recording music. It’s changed through digital recording of music. But in terms of performance, things are getting smaller and lighter, which is, of course, lovely as you get older. Much as I love vintage gear and the sound of a great guitar into a great tube amp—there’s nothing like it and never will be—there’s such a world of sound out there for people want to explore other sounds. I started using a laptop and I discovered Ableton Live, which allows you to trigger clips, and record and loop, and use computer plugin processing, a lot of which, when I started doing it, was not available in the form of pedals.

Michael Ross: It’s amazing how that’s something else that’s changed. More and more pedals are emulating the kind of processing you could previously only get in computer plugins. And just to put a plug in for one of my Guitar Moderne advertisers, Red Panda Pedals, that is kind of his whole thing. The Particle and the Tensor do glitchy and granular things that before him you could only get through using plugins. So I was using Ableton Live and then more recently, iOS apps have become incredibly powerful and do things because of the touch screen that you can’t even do with Ableton or any kind of laptop processing. I could demonstrate some of it.

Michael Ross: There’s a thing called Aum to mix various apps so I can bring them in and out if I want. Oone of the most exciting ones is Borderlands. In interest of time, I’ve already recorded some, I guess you’d call it, loops. You can do any number of loops and record them and have them separate, but as you’ll hear, there’s no sound coming out, and the sound doesn’t come out until you put one of these circles over the recorded music, and then that begins granularly processing it. If you do different sounds, you get different chords or notes coming out. You open up the circle and modify it. You can make it louder. You can change the number of processing voices. If you want it to sound more like it actually sounds, you would use less voices. Or you can use more voices. You can change how it overlaps. There’s all sorts of stuff you can do, but that’s just the beginning.

Michael Ross: What you can do is record movements. So I can record, and when I hit play it will play those movements separately. I can have it do that in any order I want. I can also record movements within the parameters, so I can have it get louder or softer. I can change the width, I can change the voices. I mean, there’s just a million things you can do with it. And this is all relatable to a key. I have it set for kind of A Lydian, so I can then play along with it if I want. And so on and so forth. I can get rid of that if I want, and just quickly show you another app. This is called iDensity. Here, I can record six separate tracks and have them all separately processed granularly. The touch screen aspect lets me actually play it.

Michael Ross: It goes on forever. I think you get the idea of what you can do. And then, with the mixer, I can t bring these in and out, mix and match them, and it goes on from there. I’m currently debating whether I just want to perform with this, or I have it also set up with an interface called iConnect. I can have this working with my laptop and Ableton Live to use the iPad apps in an effects send. That way I can record into Ableton and send anything I recorded to the iPad to be processed by the apps and returned. The possibilities are endless. It’s just a tool that you can use to expand the sonic palette that you have. I’ve experimented with using it in conjunction with an amp and regular pedals with a singer songwriter, and I would love to see more people doing that. There aren’t many at present, but I think in the future you will see more.

Nick Cody: Well, it’s mind blowing. It’s like Star Trek. If you went back to some 1950s studio and you go, “This is what the future’s gonna be like.”

Michael Ross: It’s true. You can have a recording studio where you can make a full professional record for the cost of what one reverb would have cost you back in the day. I mean, I recorded in studios with the Lexicon digital reverb that looked like something from the deck of Star Wars and, you know, with the handle on it, and you thought you’d push the handle and take off for somewhere. And they were, I don’t know, umpteen thousand dollars, and now you can have that same digital reverb in a pedal for $175 or $200.

Nick Cody: So one of the things I wanted to talk about is, you know, there’s a lot of myths where people go, There’s no money in music anymore,” which I’m not sure if this is … Well, people were proclaiming this back in the 20s, 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera, but we had an interesting conversation on that, so I’d just like you to share your thoughts on that.

Michael Ross: Well, there is no money in music anymore, but there never was any money for the vast majority of people making music. I made music for 30 years, and the only time I ever made a living at it was when it was actually cheap to live in New York City, and I was playing country and western in the 70s. I was in a bunch of, in all modesty, really good original bands, but we just never got signed. And if you didn’t get signed, you didn’t even get to make a record, let alone make money on a record. There’s umpteen stories of people who have been signed to record labels and never made a dime on records. So the good old days were not all that good to begin with. These days, as we were discussing, I feel like maybe not as many people can get rich doing it, but more people can actually make money doing it.

Michael Ross: There are people making livings playing music. It’s not easy, it never was easy, but the outlets are there. Part of it is we are going back to the early days of recording when nobody made money from records, but they were an advertisement for your live shows. So, if you can do a great live show, and you can bring people into that live show, and you’re willing to tour around, and you’re young enough, or old enough but have the constitution, to keep doing it and love to do it, you do it and you make money.

Michael Ross: There were people back in the day who weren’t that famous, like the Meat Puppets, one of my all time favourite band names, if not all time favourite bands. They were all buying houses in Texas when they were playing around, you know, because they were living, first of all, in Texas, where it wasn’t expensive, and they were making money and travelling in a van and not, apparently, putting all the money up their noses or doing many of the other things musicians do. There were plenty of regional musicians like that who had regional gigs.

Michael Ross: Maybe not so much anymore. There aren’t as many clubs where great regional musicians can have a residency and make a living, so they may have to go on the road or be good enough to make it outside their region. Things are going to change. It’s changing, it’s not going back. When things do this kind of transition, it gets rough for some people. I know really successful songwriters in Nashville, like a guy who wrote stuff for Rod Stewart and Diana Ross, lamenting that their checks have gotten smaller. Well, for a long time, their checks were really big, so I hope they put their money away. But it’s, it’s a different world. It’s just not going to happen like that anymore.

Michael Ross: But there are income streams. I mean, YouTube is a valid income stream. I just interviewed a Nashville guitar player, RJ Ronquillo, who has a YouTube channel. He was making money touring, but he wants to get off the road, so he’s going all in on the YouTube channel. To do that you have to create content, at least one or two videos a week, and you have to get it out there and sell merch. He’s doing all that, and he’s got advertising on his YouTube site. There are people making money like that. It’s just a different world, and you have to face that and figure out where you’re going to fit in it. I don’t know what else to say.

Nick Cody: A question, in all the time you’ve sort of like seeing shows and listened to albums, if you were to pick out three shows and/or three albums that come to mind today, because I know tomorrow you may have different preferences, what pops in your head where you think, actually, that was quite something?

Michael Ross: Well, because I’m three days older than water, there have been times in my life when I’ve been privy to see revolutions in music, or in guitar, as far as I’m concerned. I did get to see Jimi Hendrix, and that was pretty impressive, and it was revolutionary. And that whole time can be overrated, but there were things, certainly in terms of guitar and culturally that no-one had ever seen before, and he was one of them. I would say the guitarist after that that turned my head around, was when I went to see bassist Percy Jones play. I knew his work from Brand X. He had a band called Stone Tiger in New York at one point, and I had no idea who the other musicians were. If I did, I’d never heard them.

Michael Ross: I went down, and Dougie Bowne was playing drums, great drummer, and there was this guy, Bill Frisell playing guitar who I’d never heard of. And by the end of the show, I’m thinking, “This guy’s from Mars.” I mean, I had never heard anybody play a guitar like this. He was using a guitar synth at the time, but that was the least of it. It was just the way he played. And for years that was pretty much it, you know, in terms of people turning my head around. And then I heard Eivind Aarset, and I thought, “Oh this is a new way to approach it.”

Michael Ross: They’ve been coming pretty thick and fast since then. When I moved back to New York, I heard Oz Noy, who I was deeply impressed with as someone for whom technique is no longer an issue. He can do anything he wants to do and does really interesting things, from the way he used effects to combining blues, jazz, and Hendrix, bebop and funk in ways that I’d never heard anybody do. I was telling you there was this new guy, Rafiq Bhatia, who I just discovered and just recently saw, who is combining hip hop and Electronica and things like that.

Michael Ross: Those are the things that have turned my head around in terms of the possibilities of the instrument. That’s the main thing.

Nick Cody: And three albums, whether it’s guitar based or not. Well say three hours for today, because people always say, “My favourite three,” and you think, “Oh, wow.”

Michael Ross: That’s just so hard. I mean, you know, I mean, one that comes to mind is Coltrane’s Ballads. I mean, I’ve never been a fan of heavy bebop and Coltrane’s later stuff. I think it’s amazing music and it’s even great to learn as much as you can from it, because it teaches you so much about playing and music. It’s funny, years later after I got into that record, I read an interview with Larry Carlton, where he said that was one of his favourite records too. Because it teaches you how to play a melody, how to be lyrical and have a great tone.

Michael Ross: Boy, other albums? So, you know, I mean, that Khmer album from Nils Petter Molvaer, that turned me around. Living in Nashville now, I am totally into roots music, great blues and great country music, and, believe it or not, there is still great country music being made in Nashville. Lee Ann Womack’s last record I recommend to everybody who loves great country music. The guitar player on that record, Ethan Ballinger is this young guy from Nashville that’s very low profile, he’s been playing on these roots records, like hers and this guy, Andrew Combs’ record, which is a great record. He combines the two things that I love, roots and avant garde, because he plays solos that are completely demented and weird on those records, and, apparently, they encourage him to do it. I asked him, “How do you get away with it?” And he said, “I don’t get away with it, they like it.”

Michael Ross: He helped me discover that it actually sounds great to put your delay before the overdrive. That can be a really great sound. If you think about it, that’s Daniel Lanois’ sound. He’s running the Korg delay into an overdriven amp. It was the sound in the old days all the time, because nobody had overdrive pedals. If you were using a tape delay or anything like that and running into an amp, it was going into the amp. So it has a very distinctive sound, and I have my pedalboard set up so I can do either.

Michael Ross: There’s a guy who wrote songs for that Lee Ann Womack record, Andrew Wright. He’s a great songwriter; he wrote a song from the perspective of a tree on which lynchings were taking place, and does it in a way that is not polemic or didactic. It sounds like an old murder ballad, which is deeply rooted in country music. His records are just filled with songs like that: amazing stories told very simply, produced very simply. He’s got a great voice. He sounds like Paul Simon on occasion. It’s terrific stuff.

Michael Ross: I mean, that’s just the stuff comes to mind. Pat McLaughlin, who is relatively unknown outside of Nashville, makes the greatest roadhouse, roots, pop, soul, country records in the world. He’s one of the great, white, soul singers in a totally non-imitating black way. His band has been playing together 20 years, Michael Rhodes, Kenny Greenberg, and on some of the records, Greg Morrow on drums. They’re just amazing. I mean, his songs are sometimes almost abstract. It’s like he’ll just throw in a line that’s great but doesn’t seem to have anything to do with the rest of the song, or even barely makes sense as English, but it sounds great, and it sounds great when he sings it, and it sounds great when the band plays it. So that’s just what comes off the top of my head today.

Nick Cody: Well, thanks so much. I mean, you know, this platform is called Music For The Head and Heart, and I think we’ve covered a lot of stuff for both the head and the heart here, and we thank you for dropping by.

Michael Ross: Well, thank you.

Check out Guitar Moderne